The Pigs at Cuori Liberi (Free Hearts): Responding to Political Trauma

Original text here. Spanish version here.

It is very hard to write in the immediate aftermath of what happened in Sairano, in the province of Pavia, on September 20th. A public order to cull all pigs had been looming for two weeks over Progetto Cuori Liberi, a sanctuary for animals rescued from exploitation; activists from all over Central and Northern Italy were defending the area day and night. The previous Friday, we had already thwarted a first attempt to carry out the judgement, by chaining our bodies to the sanctuary’s gate, but the second time riot police arrived in force, determined to clear the area and allow state veterinaries to enforce the order.

It is very hard to write in the immediate aftermath of what happened in Sairano, in the province of Pavia, on September 20th. A public order to cull all pigs had been looming for two weeks over Progetto Cuori Liberi, a sanctuary for animals rescued from exploitation; activists from all over Central and Northern Italy were defending the area day and night. The previous Friday, we had already thwarted a first attempt to carry out the judgement, by chaining our bodies to the sanctuary’s gate, but the second time riot police arrived in force, determined to clear the area and allow state veterinaries to enforce the order.

To process this trauma, at least in part, I can only try to reconstruct the events and to articulate some thoughts, with the clarity that these difficult circumstances will allow. Why this euthanasia order, first of all? The background is that the African Swine Fever (ASF) has come to factory farms in Zinasco, as people feared for some time. In this area, the concentration of pigs is especially impressive: from 200,000 to 300,000 in a fraction of the Pavia province, more than 4 million in the region of Lombardy (half of the pigs farmed in Italy). ASF isn’t transmitted to humans but is extremely contagious and lethal for suidae (pigs and wild boars). Italy along with the EU took action to contrast this disease, declaring a real war against wild animals, unleashing hunting associations to decimate wild boars in the forests, even issuing decrees to employ the military alongside hunters. All of this is, evidently, in the interest of factory farming, a strategic sector founded on the unspeakable, constant violence inflicted on its prisoners, and with an environmental impact undeniable at this point. The same vulnerability of animal farming, to be true, is responsible for the spread of ASF in the Pavia area, where fields are continuously sprayed with waste from the pig industry, and animal bodies are always on the move, slaughtered or bound to a slaughterhouse.

The solution proposed by the authorities is to contain the outbreaks that emerged since the beginning of August by culling all the pigs in the farms where cases have been detected. So far, more than 30,000 killings have taken place, and the methods used have been exposed thanks to an investigation by the Essere Animali association: pigs crammed into containers and used as gas chambers, with a series of disturbing violations of biosecurity regulations meant to contain the outbreaks. In this context, where all emergency protocols are activated to defend a deadly and environmentally harmful sector amid the climate crisis, ASF unfortunately reaches the only place in the area where pigs live without being crowded and, most importantly, are not there to be exploited. The “Cuori Liberi” sanctuary, like many others in the Network of Sanctuaries for Free Animals and others (such as Ippoasi, Alma Libre, Grugno Clandestino), houses animals of various species rescued from the meat, dairy, and egg industries. The pigs living in the facility are not farmed; they receive care. When they get sick, they are treated, and in extreme cases, they are compassionately guided through their end of life, surrounded by the affection and attention of their loved ones.

The world of animal sanctuaries or refuges in Italy had recently celebrated a conspicuous victory, their legal recognition. With this fundamental step, the law acknowledges the difference between them and farms with their production logic: now animals in sanctuaries are not formally “DPA”, that is destined for food production, but are somehow equated with pets. And, if we see the relation between humans running Cuori Liberi and the non-human residents, the situation is not too different from the relation that many humans have with “their” cats and dogs (or, it might be better to say: It is similar to those relations between humans and pets that manage to be more genuine and egalitarian).

But this recognition, in the midst of a health crisis, seems to become secondary. The public administration in Lombardy orders the culling of all those sheltered in that sanctuary, both sick and healthy individuals. We mobilize immediately, guarding the surroundings day and night. Any attempts to negotiate or to find a legal solution seem to fail. After a week they show up to cull the pigs, but find people chained to the gates and dozens of activists who are gathering outside in solidarity. A few hours pass and they leave. They come back in force on September 20th, and they don’t hesitate to clear the blockade with clubs and knuckledusters. Several people are arrested, some are wounded, and worse than that what we feared happens. The gate, also blocked by some tractors, is opened and the state veterinarians can come in to kill the 9 pigs who survived the plague, mostly still healthy and without symptoms. They were killed basically in front of our eyes while the state showed off all its power in crushing the exploding rage. Even worse, they are killed in front of their human family members. Some police officers chuckle while we weep. A veterinarian laughs. They load the lifeless body on the truck in front of the crowd. In the meantime, the usual repertoire of sexist slurs to women, of ableist insults to those who resist them. A cruel lucidity in clearing the sanctuary out, where laughter hurts more than their batons. Even though I experienced more heinous situations of police brutality, none of them was as cruel as seeing people carried away who had only their body left to protect pigs sentenced to death.

People sing “Bella ciao”, maybe with a bitter desire for continuity with the stories of human resistance recognized and celebrated by a leftist movement that is still too anthropocentric: a continuity that we would like existed but that sadly doesn’t exist, if not in our hearts, because here there are only antispeciesist activists, as always. A handful of people, all a little crazy. It is a moment of mourning, but also of anger. After “Bella ciao,” it is the time for “Tout le monde déteste la police”: here the continuity is perhaps more real, they make it very apparent, pushing us back with their shield, arresting random people, preventing the ambulance from going ahead to aid a comrade, identifying and intimidating activists at the emergency room. They leave after violating in every possible way the biosecurity measures that they were there to enforce, while we are doing our best not to spread the disease. We weep and hug each other.

It’s a shock. It was a shock from the beginning because that euthanasia order was already dangerous as a legal precedent. It is even worse now that it has been carried out. They can come into a sanctuary and kill its inhabitants. Only the struggle, only our bodies can avoid it, and this time they weren’t enough. When will it happen again? I would like to understand this trauma that paralyzed us. Not only the massacre in front of our eyes. A comrade says that our movement is “naturally” more radical, because “when we lose they kill somebody”. It is true, and this is why we were ready to do everything. But I am beginning to think that there is more.

This shock is rooted in our liberal delusions, a slap in the face of our beliefs about basic rights in a democracy. In theory, we know well things are not as they tell us: the liberal state doesn’t truly guarantee, always and in any case, formal liberties like not having police forces breaking into your home. We know that democracy, when necessary, can rapidly turn into fascism. But deep down, we have interiorized that, if you have at least the privilege of being white and a citizen, there are some limits. To see them overcome in a few days is a great shock. In some ways, a shock comparable to the beginning of the pandemic when – beside our opinion on the measures taken by the government – we immediately found the army on our streets, and the “sacred” freedom of movement (“sacred” only for full citizens, as I said) was set aside. The true face of the state becomes visible in certain circumstances, and as antispeciesists we should know that well.

But now it is declared: this is what they are willing to do to protect an unsustainable economic sector. They can enter private homes and kill those who live there. The refuge, in fact, is more like a private home than a public place. The refuge is a multi-species family. And the comparison with pets (“sooner or later, they will come to kill the dogs in our homes”), which we used as a rhetorical device until now, is no longer so imaginary. Another element of this political trauma: there are no safe places. This is what we had always thought about refuges/sanctuaries: safe places, oases of peace for refugees who bear the wounds of a past of slavery on their bodies. What will be the next safe place that turns out to be violable? How will we respond?

I keep wondering how we have responded. If we have done enough, what the balance of power is, what this emergency mobilization means. In fact, for a long time, the antispeciesist movement has primarily produced responses to emergencies. In doing so, it politicizes them and exposes the contradictions of an anthropocentric, neocolonial, extractivist production system. But it remains within an emergency. It responds to it with a determination and desperation that the enemy cannot fully comprehend, which is a good thing. And it does so by shuffling the cards, in some respects. I will mention two elements that have struck me in this regard. The first is the political prominence of refuges/sanctuaries. Years ago, the animal movement looked at sanctuaries/refuges exclusively as places for the care of individuals rescued by more meaningful parts of the movement (associations, campaigns against vivisection or fur, the Animal Liberation Front). Nobody expected the sanctuaries to take position, to be a source of reflection, of intersectionality. All these elements are now at the core of many sanctuaries. We could even say that today animal sanctuaries are the driving force, the beating heart of antispeciesism. The second is the gender aspect of the mobilization. For two weeks, the resistance against the animal health bureau and its henchmen was primarily fueled by and led by women comrades. Perhaps this may have bewildered some cisgender heterosexual boys, but it’s safe to say it was about time, in an environment where the female component has always been in the majority, but leadership has been predominantly male. The immediate response to the shock also overwhelmed antispeciesist theory, overtaken by events in the blink of an eye. And so, people who believed they were divided by theoretical differences found themselves united and close in desperate sisterhood. Thanks to those who were there, each in their own way. Everyone went as far as they could, as it should be, but some absences were bitter.

Certainly, however, mourning needs to be processed, and to process it, there is a need to fight, not only to respond to the attacks but also to launch counterattacks. And there is a need for accomplices, especially in those sectors of the environmental movement that have recognized the importance of this battle. Once again, as with COVID, speciesist capitalism generates diseases, nurtures them in the overcrowded bodies of animals where profit reigns, and then fails to manage or contain them. Instead, it shifts blame and burdens onto those who have no say: vulnerable groups, the poor, workers, boars, pigs. In the area where 30,000 animals were culled, pigs are ten times as many. In the Po Valley, in certain extensive areas of Lombardy and Emilia Romagna, the animal population in farms exceeds the human population. And the fields around the Cuori Liberi refuge, which I have come to know in recent days, are literally a hell. The waste, the smells, the lands devastated by chemicals, surrounded by concentration camps for pigs, constantly assault our senses with a stench of death that we have learned to deny in the face of the slices of salami at the local supermarket.

Certainly, however, mourning needs to be processed, and to process it, there is a need to fight, not only to respond to the attacks but also to launch counterattacks. And there is a need for accomplices, especially in those sectors of the environmental movement that have recognized the importance of this battle. Once again, as with COVID, speciesist capitalism generates diseases, nurtures them in the overcrowded bodies of animals where profit reigns, and then fails to manage or contain them. Instead, it shifts blame and burdens onto those who have no say: vulnerable groups, the poor, workers, boars, pigs. In the area where 30,000 animals were culled, pigs are ten times as many. In the Po Valley, in certain extensive areas of Lombardy and Emilia Romagna, the animal population in farms exceeds the human population. And the fields around the Cuori Liberi refuge, which I have come to know in recent days, are literally a hell. The waste, the smells, the lands devastated by chemicals, surrounded by concentration camps for pigs, constantly assault our senses with a stench of death that we have learned to deny in the face of the slices of salami at the local supermarket.

This grief will follow us, from now on, in every struggle that will come.

Pumba, Dorothy, Ursula, Bartolomeo, Carolina, Mercoledì, Crusca, Spino, Crosta: sorry that we did not make it.

By Puppy Riot

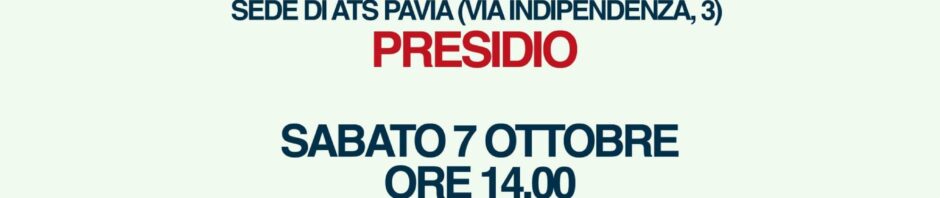

* A national march will be held in Milan on October 7th. You can follow Rete dei Santuari di Animali Liberi on social media for updates on the next demonstrations related to this issue.